Julia, the main character, is known for being "bastante perezosa" at the beginning. She likes to spend her weekends in her pajamas, lounging on the sofa and watching TV. Her Tio Paco comes to visit and suggests an excursion to the snowy mountains. Julia finds everything wrong with this idea. I love how the author describes her attitude:

Era evidente que la excursión no le hacía

gracia. Al bajar del tren, cuando la

brisa helada le tocó el rostro, su malestar fue aún mayor. Con cara de pocos amigos, como si estuviera

enfadada, comentó: --¡Oh, qué frío!

Just as she is feeling even worse for the cold, her uncle starts a snowball fight with her. The whole family joins in until Julia is laughing so hard she isn't thinking about the cold or being at home watching television. On the way home, she even asks her uncle about the possibility of returning soon.

If this was the first time I was introducing the concept of character change, I would use my Emoticons cards. Depending on your students' vocabulary, it might be necessary to take one class period to just familiarize them with the vocabulary terms for emotions. They could sort the emotions according to positive or negative feelings. You might have them draw an Emoticon out of a bag and tell their partner about a time they felt that emotion.

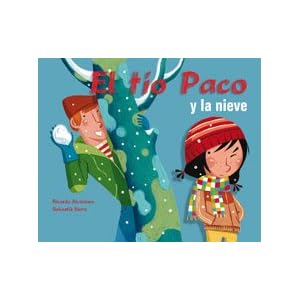

When students are familiar with these emotions, read aloud the book El tío

Paco y la nieve. Pass out the Emoticon cards and ask students to identify which of these emotions was demonstrated by Julia during the story (enojada, frustrada, sorprendida, contenta, emocionada). Once students have identified the emotions, make a list on chart paper in the order they are shown in the story. Return to the story and model rereading to find text evidence that supports our conclusion that Julia feels a certain emotion. Next to each emotion in the list, write key words or phrases from the text that provide evidence. Repeatedly use the sentence, "Sabemos que Julia se siente ____, porque el texto nos dice que..."

This book deals with very simple but very relevant emotions and change within a character. Other books will delve much deeper into character development and lifetime change. El tío

Paco y la nieve is not about heart-wrenching emotional change! It does, however, present a simple structure for understanding plot and character. As your students apprentice with this book and its simplicity, they will soon be able to move on to deeper, more layered texts.

For more info on teaching about character change and motivation, see this ReadWriteThink.org lesson plan.

If you would like to use a Spanish version of RWT's graphic organizer, you can find my version here.

I hope you and your students enjoy this little gem of a book!

![What Can You Do with a Paleta / ?Qu? Puedes Hacer Con Una Paleta? [SPA-WHAT CAN YOU DO W/A PALETA] [Spanish Edition] [Hardcover]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51rP33LJo5L._SL500_AA300_.jpg)

![What Can You Do with a Rebozo? / ?Qu? Puedes Hacer Con Un Rebozo? [SPA-WHAT CAN YOU DO W/A REBOZO] [Spanish Edition] [Paperback]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/514XS%2ByPD5L._SL500_AA300_.jpg)